“Walking” cells

In order to understand this, we need to imagine the cancer cells in a tumour. These cells, which are equipped with small extensions (which we will call feet), are grouped together on fibres (the path). As metastases develop, cancer cells migrate out of the tumour along these fibres into blood vessels, from where they spread throughout the body. In simple terms, it is as if these cells are 'walking' along the fibres. A protein found in these fibres, fibronectin, seems to facilitate this migration.

An uncanny resemblance with PACMAN®

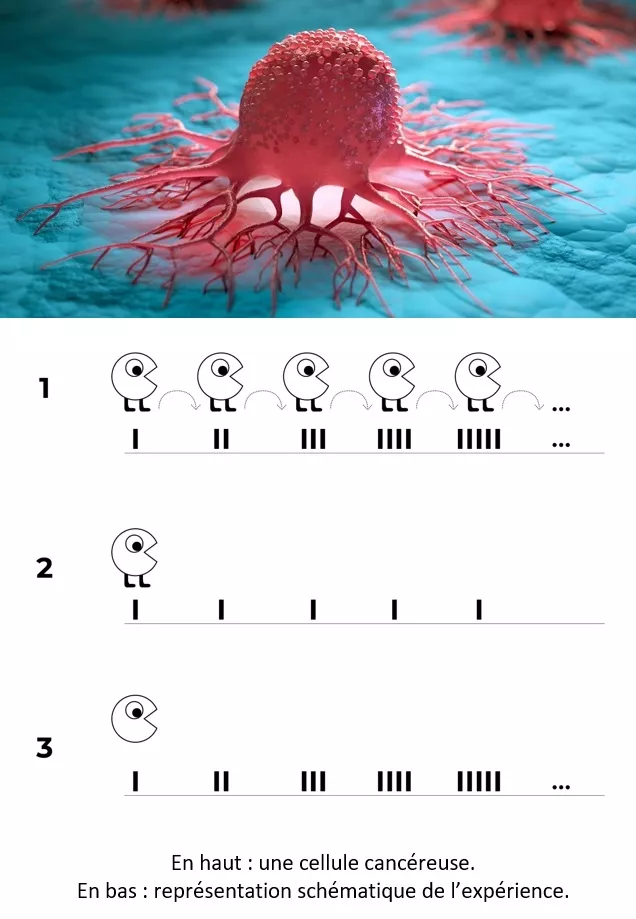

The research project involved metastatic breast cancer cells. As shown in the illustration, a first experiment was carried out in which a fragment of fibronectin was distributed in an increasing gradient on a gold surface. Cancer cells were then deposited on it and found to move in the direction of the gradient (1). This is a bit like the arcade game PACMAN®, the project's acronym, in which PACMAN® moves by swallowing pellets. However, if this experiment (2) is repeated, keeping the concentration of the fibronectin fragment constant, the cells do not move. The researchers then 'removed' the feet from these cells (3) and found that the cells no longer migrated. These feet are therefore an essential component of metastatic cells.

A 'proteomic' study of the footless cells identified the foot recycling process as a process involved in the ability of cancer cells to migrate.

This study on understanding these fundamental mechanisms could therefore, in the long term, make it possible to detect metastases at an early stage of the disease or to study ways of preventing a tumour from releasing metastases and thus reducing the risks of complications and mortality associated with this type of cancer.

A former UNamur PhD student, Sophie Ayama, who did her thesis on the subject, was a finalist in My Thesis in 180 seconds (MT180) in 2019.