This is the result of four years of intense work by a team of researchers in linguistics and computer science from UNamur.

This is a world first that offers a powerful, easy-to-use tool that is freely accessible to a wide audience: deaf children, their families, teachers, translators and interpreters.

In French-speaking Belgium, the French sign language of Belgium (LSFB) is used by about 4,000 people. The idea of creating a bilingual LSBF-French dictionary originates from the collaboration that UNamur has been maintaining for almost 20 years with the bilingual classes (French - LSFB) founded by Ecole et Surdité in Sainte-Marie Namur.

“In our contacts in the field, in schools for example, or in our research work, we noticed that linguistic tools for bilingual sign language/French translation were few and had limited functionalities. Until now, these tools have consisted of lexicons compiling signs and their meanings in French, or the online dictionary, which also offers a definition of the signs in LSFB, a few examples where the sign is used in a sentence and information on the etymology of the signs," explains Professor Laurence Meurant, linguist and head of the Laboratoire de langue des signes de Belgique francophone (LSFB-Lab) at UNamur.

Laurence Meurant and her team then began to dream of a more effective tool, inspired by the Linguee© principle, which could help users of all ages. It would enable users to understand and use words and expressions or signs in various contexts, taken from spontaneous conversations, and could be questioned directly in sign language. In 2018, a multidisciplinary team of linguists and computer scientists from UNamur came together to tackle this scientific and technological challenge.

Four years later, thanks to the financial support of the Baillet Latour Fund, a pioneering tool is operational: a new bilingual LSFB-French contextual dictionary.

How the dictionary works and its advantages

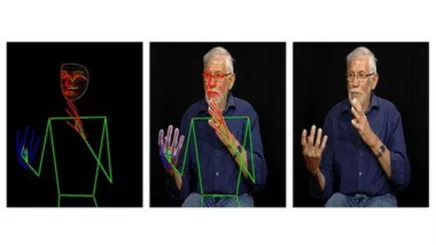

The dictionary developed by UNamur can be queried in both languages. In concrete terms, the user can sign in front of the computer camera, and he will obtain the word he is looking for and the contexts in which it can be used. Conversely, the user can enter a word into the dictionary search engine and obtain its translation into a sign, as well as a list of suggested uses for the sign in the form of videos. These features are currently unique in the world.

This dictionary is based on a very rich database of sign language, unique in the world. It uses the productions in French-speaking Belgian sign language (LSFB) of one hundred signers, totalling more than 80 hours of filmed conversations and their translations into French to create a repertoire of bilingual texts. This corpus is the result of several years of translation and annotation work, sign by sign, carried out by the LSFB-Lab team at UNamur. This database will continue to be fed by the UNamur teams in order to continuously enrich the dictionary.

Thanks to a state-of-the-art recognition system, the dictionary is able to detect, recognise and translate the sign submitted by the user in a very short time. It works in any environment (no need to be in a recording studio or behind a green background, for example). The tool can therefore be used directly by pupils and teachers in their classrooms or at home.

This new tool is available on a digital platform that can be accessed free of charge from a tablet or a computer. The tool is intended to be accessible to everyone and everywhere.

88h

videos

4,600

different signs

18,872

translated sentences

The technological challenges

In order to develop this new dictionary, many challenges had to be met, both linguistically (design and feeding of the corpus, as mentioned above) and in terms of computing. The success of this project is therefore largely due to the excellent collaboration and the important complementarity between the linguists of the NaLTT institute and the computer researchers of the NADI institute of UNamur.

"This tool first of all required web engineering work to create a high-performance, user-friendly platform," explains Anthony Cleve, professor at the Faculty of Computer Science and pilot of this project alongside Laurence Meurant. "But we also called on our expertise and the latest research advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence, as well as human-machine interaction and data engineering, to achieve this totally pioneering and innovative result.

Development perspectives

- International development: The technology implemented can be applied to other speech-language-sign language pairs. Tests have already been carried out on the Dutch language-sign language pair, thanks to a collaboration with Prof. Onno Crasborn (Radboud University of Nijmegen). The entire signing community in Europe, and indeed the world, could therefore benefit from this innovation.

- Technological development: "Error monitoring will be set up so that the recognition system for detecting the user's sign is constantly improved and refined," Anthony Cleve also says. "This will not only provide even more accurate and precise translations but also further enrich the corpus," he continues. In addition, the computer researchers are studying how the tool will be able to segment a sentence in LSFB into individual signs. On this basis, the development of tools for simultaneous translation from one language to another could be aimed at.

The UNamur expertise in sign language

UNamur is a pioneer in the linguistic study of LSFB. Its Sign Language Laboratory in French-speaking Belgium is unique in Belgium. It works closely with the ASBL École et surdité and the Centre scolaire Sainte-Marie Namur, which has included groups of deaf children in hearing classes since the beginning of the year 2000, offering these pupils a bilingual education.

The UNamur research team

It is not only interdisciplinary (linguists and computer scientists), but also intergenerational with senior profiles (academics and post-doctoral fellows), and quite junior (students). It is also inclusive, since hearing and deaf people participate in this project.

The team: Laurence Meurant (LSFB-Lab), Anthony Cleve (Informatics), Benoît Frénay (Informatics), Bruno Dumas (Informatics), Sibylle Fonzé (LSFB-Lab), Bruno Sonnemans (LSFB-Lab), Alice Heylens (LSFB-Lab), Maxime Gobert (Informatics), Jérome Fink (Informatics), Maxime André (Informatics), Pierre Poitier (Informatics), Loup Meurice (Informatics)